In the pandemic absence of public liturgies, perhaps you have found a renewed relevance to the ancient psalms of the Hebrew Bible. Although never fully out of style, they tended to pass us by during Mass, scarcely noticed, as the congregation rifled through the latest file of its collective short-term memory, searching embarrassedly for the response parroted just moments before. With all their anguished cries for deliverance, protection, succor and mercy, the psalms suddenly sound again custom-made for our own distressing situation. So fitting are they to the tightness of crisis that we Jesuits of Guelph agreed unanimously in March to pray Vespers together in choir. You need only the slightest understanding of the spiritual life of your average Canadian Jesuit to appreciate the magnitude of this unlikely concession to communal prayer. Dire measures for dire times, indeed!

Composed in hardship for hardship, the plaintive, often desperate lines of many psalms have accompanied the persecuted, the imprisoned and the morbidly perplexed throughout nearly three millennia. Even Jesus, at his darkest hour in the gospels of Matthew and Mark, dedicates his final breaths to the recitation of the first devastating words of Psalm 22. My “shield,”, my “rock,”, my “refuge” —, such are the psalmist’s names for God when all looks black and hopeless.

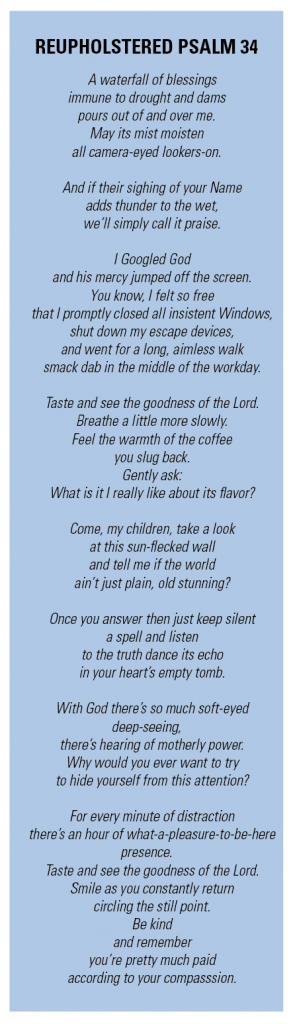

While the amplitude of the psalter allows for tailored application of one or more of the 150 psalms to any given situation, they are best read and understood together as an integral body of scripture. That is, to truly grasp one, you need to have a decent hold on them all. Only in their integrity does the power of their individuality fully emerge. Lines such as “Lord, how long will you look on? Save me from roaring beasts,” from Psalm 35, never stray too far from lines such as “Taste and see the goodness of the Lord,” from Psalm 34. Were all lines expressions of anxiety, the psalms would not instill in us the trust they do. Were they all honey and sunshine, they would taste as flat as artificial sweetener in the bitterness of tribulation.

On the other hand, as soon as the good life bottoms out and our fictions of security reveal themselves in their full, terrifying vacuity, then we best cleave to the gratitude and praise so colorfully present in psalms such as number 34. “Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.”. Who on earth can do that in the stranglehold of a global pandemic? Precisely here the ingenious imagination of faith enters, calling creative attention to reality as it is and as it could be.

“With God there is so much soft-eyed deep seeing, there’s hearing of motherly power.”

What has popularly become known as mindfulness is a secular version of the contemplative Christian attitude that operates whenever the human person deeply experiences her current embodied reality. Every sensation is proof that we are alive and receptive. By spending reverential time with the million little divine manifestations constantly occurring in our sensitive bodies, we can’t help but “taste and see that the Lord is good.”

It is astonishing that Teilhard de Chardin, SJ, emerged from the bloody trenches of World War I with a profound sense of the divinity that animates all creation. He found God where only death and disaster seemed to dominate. Similarly, Viktor Frankl notes: that “As the inner life of the [concentration camp] prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before.” Frankl recounts several occasions when, cold, sickly and starving, he and other prisoners unexpectedly were overcome with awe and gratitude at the sight of a splendid sunset. Systematically numbed by cruel abuse, suddenly their senses were quickened by attentive presence to reality. These were salvific moments of embodied transcendence.

So dare to count your blessings in the days of crisis. Take time to taste and see. This is not irresponsible escapism or self-delusion. This is vital resistance to the oppression of disappointed claims of ownership and associated despair. It is the incarnational practice of feeling God in all things.

Greg Kennedy, SJ, is a Jesuit priest working in spirituality and ecology at the Ignatius Jesuit Centre in Guelph, Ontario. His Reupholstered Psalms: Ancient Songs Sung New was released by Novalis Press in March 2020.

Greg Kennedy, SJ, is a Jesuit priest working in spirituality and ecology at the Ignatius Jesuit Centre in Guelph, Ontario. His Reupholstered Psalms: Ancient Songs Sung New was released by Novalis Press in March 2020.

Greg Kennedy, SJ, is a Jesuit priest working in spirituality and ecology at the Ignatius Jesuit Centre in Guelph, Ontario. His Reupholstered Psalms: Ancient Songs Sung New was released by Novalis Press in March 2020.